History and Perspective

Although the Sound Archives were not established until 1920 as the Sound Department of the Prussian State Library, recordings date back to 1909. That was when the language teacher Wilhelm Doegen, 1877–1967, began to produce language records for teaching languages at school. His technical basis was the gramophone, developed in 1887 as an improvement on the phonograph, which had been invented ten years earlier.

The Prussian Royal Phonographic Commission

Doegen’s project was extended substantially with the establishment in 1915 of the Prussian Royal Phonographic Commission, which as an interdisciplinary research group headed by the psychologist and musicologist Carl Stumpf set itself the target of recording the languages and traditional music of soldiers interned in German prisoner of war camps. When the Commission was dissolved the phonographic music recordings found their way into the phonogram archive founded by Stumpf in 1900 at the Berlin Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität (today’s Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin), which had focused from the outset on music recordings and is seen as the first center of German music ethnology. The Berlin Phonogram Archive is now housed in the Ethnological Museum, one of the State Museums in Berlin, and holds inter alia 1,030 music recordings on wax cylinders that the Phonographic Commission had made in German prisoner of war camps between 1915 and 1918.

The Sound Department at the State Library

The language and music gramophone recordings made in World War I German prisoner of war camps were combined with Doegen’s language learning records and a collection of recordings of the voices of important public figures as a standalone collection, the Sound Department of the Prussian State Library. Doegen took over as head of the department, having pressed for its institutionalization and at least accepted the separation of the phonographic music recordings, which included instrumental music and song. The foundation of the Sound Department in 1920 can be considered to have been the origin of today’s Sound Archives. The Sound Department also included Ludwig Darmstädter’s collection of voice recordings, begun in 1917, which complemented Darmstädter’s collection of autographs from the history of science by documenting the voices of famous people – mainly male politicians, scientists and artists.

Both collections were subsequently systematized and enlarged. In addition, recordings of people in situations of coercion, such as prison inmates, were repeatedly made.

A further collection area was the documentation of German dialects using the standardized Wenker sentences as a textual basis. Recording sessions were held in the 1920s in Germany, Switzerland, Ireland and Latvia.

It can be said of all collection areas that the prevailing ideal, which evolved in Europe and North America in the second half of the nineteenth century, was that of encyclopedic collecting. The focus was on recording, documenting and preserving, leaving evaluation to future generations. While the voices of public figures concentrated on individuals and veritably cast them in heroic roles, recordings of languages and German dialects saw the individual as characteristic and typical of a language group. Mainly male voices were recorded, understandably in the context of prisoner of war camps, but this evident selection criterion runs counter to the pretension to be complete and representative.

Transfer to the University of Berlin

In 1930 Doegen was accused of personal enrichment by selling records, of scientific inadequacy and of anti-Semitic insulting of employees. He was cleared on all charges but his position was weakened. He was first suspended and in September 1933 retired on the basis of the infamous Nazi law on “restoration of the professional civil service.” In retrospect Doegen saw himself as a victim of his anti-Fascist views, although he did not distance himself from the Nazi regime in his published work and a 1941 publication bears the hallmark of racist abuse (cf. Stöcker 2008, 132f).

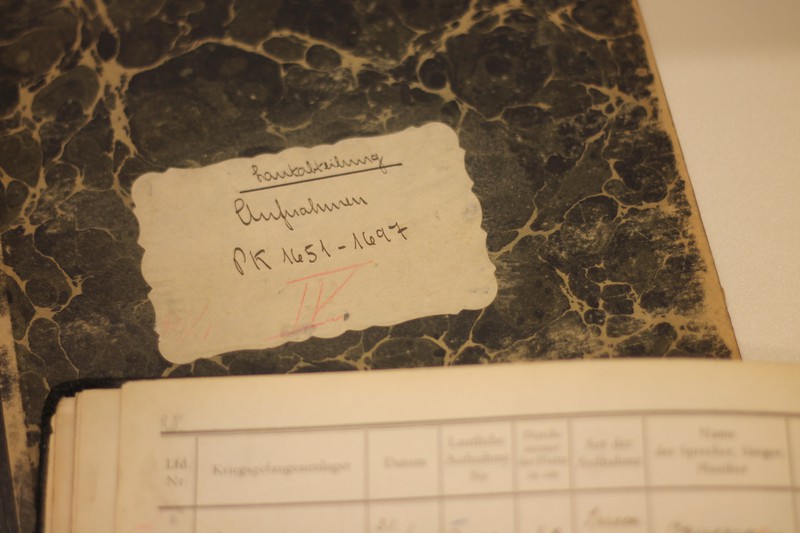

The administration of the Sound Department was transferred to the University of Berlin in 1931. The African studies and phonetics specialist Diedrich Westermann took over as head of the collection in 1934, transforming it into a center of phonetics teaching and research. In 1935 it was divided into three departments: linguistics (headed by Westermann), music (headed by Fritz Bose) and a phonetics laboratory (headed by Franz Wethlo). As in World War I, recordings were made in prisoner of war camps in World War II until 1944. While intensive work has been undertaken on recordings made by the Phonographic Commission in World War I prisoner of war camps, especially in WWI centenary year 2014, less attention has been paid to Sound Archives activities in the Nazi era. We now know the master copies of all sound recordings of which shellac records still exist were lost during World War II.

The Sound Archives in the GDR Era

After 1945 the Institute of Sound Research was restructured more than once. Fundamental structural reform as part of the 1969 university reform led to it being renamed the Department of Phonetics and Linguistics in the Rehabilitation Pedagogics and Communication Science section. Relatively little is known about the phonetics tape recordings made during this period and still stored in the Sound Archives. That tallies with the relatively marginal concern with GDR era collections. Furthermore, these recordings have not yet been digitized and the Sound Archives have no digitization facility for them.

In the mid-1970s the music ethnologist Jürgen Elsner realized the value of the collection that had been accumulated and helped to preserve it. After an extensive review of the stocks in the 1990s Dieter Mehnert presented a first inventory report on the Sound Archives.

Development and Use as a Historic Archive Since the 1990s

Steadily increasing attention has been paid to the Sound Archives since the 1990s. It was largely due to the digitization of the recordings and their storage in an Internet-enabled database by Jürgen Mahrenholz, custodian of the collection from 1999 to 2007. Contexts of this development are the conceptualization of archivology during this period and the increasing attention paid to university collections.

The film-maker Philip Scheffner dealt in detail with individual recordings in his 2007 film The Halfmoon Files. A Ghost Story. For the film he traced individual Indian speakers at the prisoner of war camp in Wünsdorf. They were no longer seen as typical representatives of languages but as historical individuals and attention was expressly paid for the first time to the contents of recordings and to personal statements. Subsequent usage scenarios frequently relate to these modes of access. Describing the Sound Archives as a “sensitive collection” (Berner/Hoffmann/Lange 2011) in that the recordings were made in precarious situations such as those of inmates in a prisoner of war camp changed the perspective on the Sound Archives, as did the attention paid to the technicalities of sound recording and the interference it involved. Doegen’s programmatic approach envisioned research into ‘foreign peoples’ (or indeed “our enemies”). In recent years the focus has instead been on opening up the recordings with actors who have other cultural backgrounds and on productively relating different disciplinary and cultural perspectives to one another.

Status quo 2022 and perspective

The Lautarchiv is the only collection of the Humboldt-Universität that has moved completely into the Humboldt Forum on Schlossplatz in the course of 2022. Presentations in exhibitions are planned as well as cooperations with the ethnomusicological department of the Ethnological Museum. The Phonogrammarchiv and the Lautarchiv of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin are now united under one roof. In particular, the shared history in the recording activities of the Phonographic Commission from 1915 to 1918 will result in numerous cross-connections and opportunities for cooperation.

The Humboldt University’s goal in moving the Phonographic Archive to the Humboldt Forum is by no means to museumize the collection, but rather to further develop its character as a research and teaching platform that is also open to a general public.

Further Information

A comprehensive history of the Sound Archives is not yet available. Important contributions toward an overview that also make the shifts in perspective for the Sound Archives since the 1990s understandable are: Mehnert 1996, Ziegler 2000, Mahrenholz 2003, Stöcker 2008, and Lange 2017, (“Archive, Collection, Museum”)(cf. publication list on this website). There is a chronology of important data on the history of institutions and collections under the heading “Chronology.”